Andy Clark and David Chalmers have argued for what they call the extended mind. The theory states, roughly, that the mind is broader than body. Or as David Velleman once colorfully explained it to me, that the mind ”leaks out of the ears.” Parts of the world can, according to an extended mind theorist, become parts of the mind. Which parts of the world? Any parts, really, depending on how you interact with them, but common examples include wristwatches, notebooks, and iPhones.

Strictly speaking, the extended mind theory is really two theories. One is of extended belief, the other of extended calculation. Extended belief is storing beliefs in, say, a notebook, instead of in memory. Extended calculation is multiplying 543 by 7 with a pen and paper instead of in the head. An extended mind theorist calls the notebook and the pen and paper in these examples parts of the mind. At least, this is what an extended mind theorist would have said several years ago. Clark and Chalmers have recently distanced themselves from the language of parts, and Clark now says instead that notebooks, iPhones, and the like might count as “being appropriately integrated into our cognitive profiles.”

I think the vocabulary of the extended mind theory is getting messy. This makes the theory harder to understand, and harder to argue clearly about. What’s really unfortunate is that “part” and “extension” are two perfectly good words–it’s just that no one is using them sensibly. I want to clarify the distinction between part and extension by setting aside the extended mind theory, and considering the extended body instead. There is a straightforward sense in which parts of the world can become extensions of–not parts of–the body. Once I have explained how this works, I can present the extended mind theory in a new way. On my view, extended calculation turns out to be not just plausible but commonplace, while extended belief turns out to be something of a mystery.

Let me introduce two concepts, both best understood functionally. They are distinct from one another, and they are distinct from mind. The concepts are subject and animator. What does a subject do? It has perceptual experience. Anything that has perceptual experience is a subject. I am one, so are you, and so is my cat. I am limiting us to perceptual experience here, even though there is much more to experience than perception. I take up another kind of experience later.

Are mind and subject the same concept? No. A mind may play the role of a subject, like Sean Connery plays the role of James Bond, but this does not make them the same. I have just given a complete functional description of subject: It has perceptual experience. To give a complete functional description of a mind, I’d have to say much more, and I probably couldn’t say enough. Minds have beliefs and desires. Minds reason. Minds calculate. The list, I am sure, goes on.

What does an animator do? Raise your right arm. Now your left. Now dance around the room. You, in your capacity as animator, are animating your body. Anything that animates a body is an animator. You are one, so am I, and so is my cat. But again, animator is not the same as mind, nor is it the same as subject. You could be a subject without being an animator if, for instance, you were completely paralyzed.

Note that animating is not the same as moving. I animate my body often, which causes me, when I am clothed, to move my clothing. But I do not often animate my clothing. The relation between an animator and what he animates, and between a subject and what he experiences with, is best expressed in the language of embodiment.

Sydney Shoemaker distinguishes between embodiment of three kinds. The first–biological embodiment–is familiar, because we are all biologically embodied in our own biological bodies. To be biologically embodied is just to be connected to a body by certain types of biological processes. Which processes? I don’t know. Assuming physicalism, the answer is perhaps easy; but if dualism is true, well, it may not be so easy. Let’s let that be. Biological embodiment is not the only way of being embodied, and it is the least interesting.

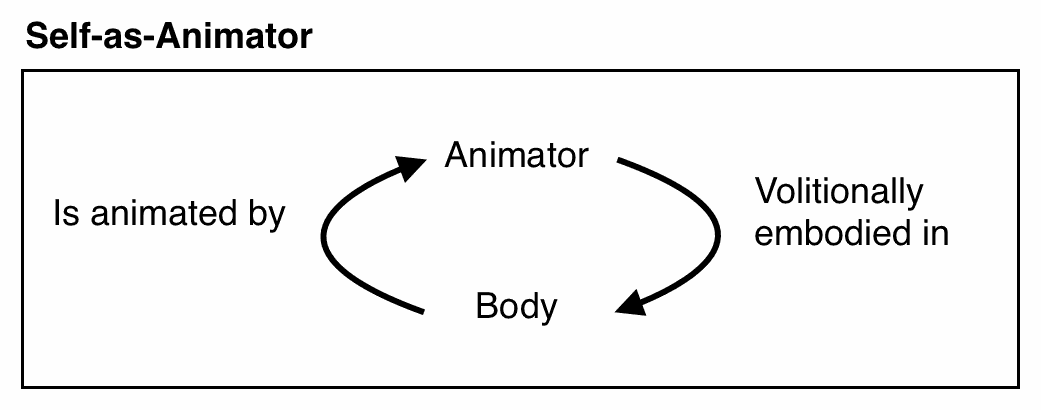

Someone is volitionally embodied (in a certain body) “to the extent that the volitions of the person produce in that body movements that conform to them” (Shoemaker 117). Volitional embodiment is not an all-or-nothing affair. The more a body obeys your volitions, the more you are volitionally embodied in it. An olympic gymnast, then, is more volitionally embodied in his body than I am in mine, because his body would obey a volition to backflip. Mine would not.

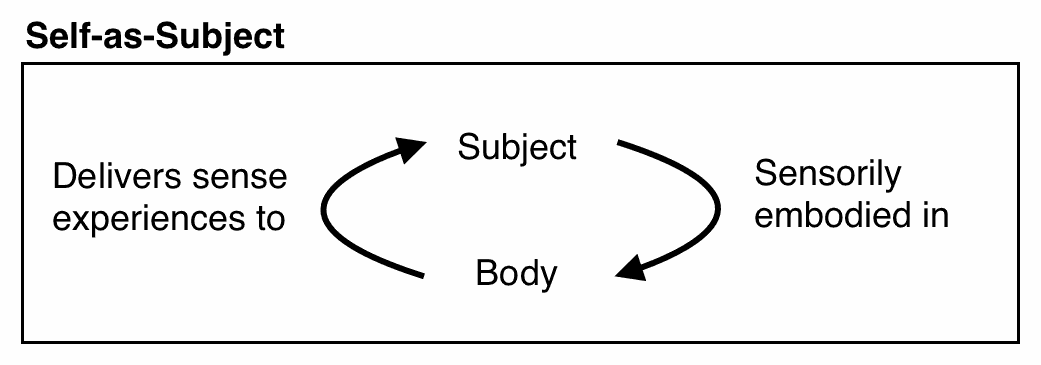

Someone is sensorily embodied to the extent that his body’s interactions with his surroundings produce “sense experiences corresponding to, and constituting veridical perceptions of, aspects of those surroundings” (Ibid). Most of us are sensorily embodied in our biological bodies to roughly the same extent, but I am better sensorily embodied in my body than someone deaf and blind is in his.

There are two important differences between Shoemaker’s understanding of embodiment and my own. First, he writes of embodiment as it applies to people. When he says “someone” is volitionally embodied, he means “a person.” I think embodiment applies to people, but only contingently. That is, I think volitional embodiment applies to animators, and that sensory embodiment applies to subjects. Both volitional and sensory embodiment apply to people, because people are subjects and animators. Something else that was a subject and an animator would be volitionally and sensorily embodied.

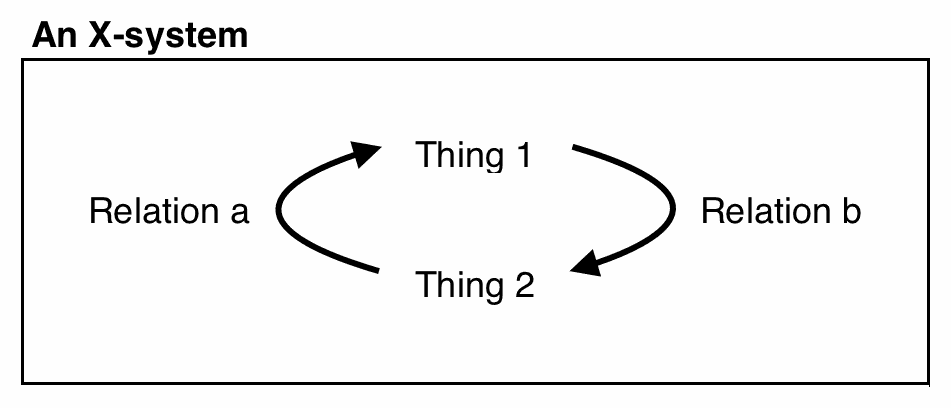

Second, Shoemaker writes of embodiment in a biological body. There is no reason that one could not be volitionally or sensorily embodied in something else, and in fact this happens often. Examples are forthcoming, but first let me make quite clear the relation between embodiment, animator and subject. When I see diagrams that look like this …

… I am reminded of high school chemistry lessons about the Krebs Cycle. I disliked those lessons. So it surprises me to say that I will now present a few such diagrams.

A subject is sensorily embodied in a body, which body delivers sense experience to the subject. What I am describing here is a system, like the one above, and it could use a name. I call it the self-as-subject.

Likewise, an animator is volitionally embodied in a body, which body is animated by an animator. I call this system the self-as-animator. It looks like this:

I, in my role as animator, am part of a system called the self-as-animator. I, in my role as subject, am a part of a system called the self-as-subject. I am about to argue that the body is extended in both of these systems. What I mean by “extended” I haven’t said precisely, but the idea is that parts of the world, loosely speaking, become parts of the body. Strictly speaking, it’s that parts of the world become extensions of the body. The difference between part and extension will be clear in a few paragraphs.

In his paper “Bodies, Selves,” Velleman describes the process of learning to control an avatar in the game Second Life. Anyone who has played a video game that involves controlling a character knows roughly what this is like. At first, it is laughably difficult. Your child or younger sibling will watch and say, “Man, you suck.” At first, you must place your attention on how to manipulate the input device (a keyboard, a joystick, etc). If you want to make your character jump, you focus on pushing the forward arrow and the ‘A’ button. Whoops, your character threw a punch instead. To jump, you must push forward and ‘B’.

With practice, though, you need no longer focus on an input device. An experienced player can focus instead on his character. His volition will not be to press forward and ‘B’; his volition will just be to jump.

Lest you think this sort of thing only happens to gamers, consider an Olympic ice dancer and a first-time skater. The novice wonders what on Earth are these strange skates attached to his feet, and why do they make getting from here to there so awkward? He animates his feet, which in turn move the skates, which in turn move his whole body in bizarre and possibly dangerous ways. Whereas the Olympic ice dancer just dances.

Perhaps a better example is of writing by hand. Recall learning to write. Your volitions were toward gripping this strange pen-thing properly, your focus on how it responded to the movements of your fingers. But consider the phrase, “With a stroke of the pen, the President signed health care reform into law.” Why don’t we say “With a stroke of his hand … ”? We don’t say this because no writer, when writing, has volitions toward his hand. A writer’s volitions are toward his pen.

Though a writer’s pen responds to his volitions much as his body does, a pen is not part of his biological body. Instead, it plays the role of his body in the system called self-as-animator. Call anything that plays the role of body, but is not body, an extension of the body.

Just as the body can be volitionally extended, it can be sensorily extended. Think about what it’s like when someone brushes against the sleeve of your coat. Even if he doesn’t touch your arm at all, you feel it. Where do you feel it? Not it in your arm–you feel it in your coat. Your coat, obviously, is not a part of your biological body, and you do not have nerve endings in it. But neither do you have nerve endings in the outermost layers of your skin. You feel in both nonetheless, because you are sensorily embodied in them. Your skin also happens to be part of your body, while your coat just plays the role of your body in the system called self-as-subject. The coat is thus an extension of your body.

A coat illustrates not just extended sensory embodiment, but also how sensory and volitional embodiment can come apart. Though you are sensory embodied in your coat, the degree to which you are volitionally embodied in it is negligible. You almost never direct volitions toward a coat, or sweater, or any ordinary article of clothing. You feel with them, but you under most circumstances you do not animate them. They just happen to move when you animate your body. To animate your clothes, you’d need to have volitions toward them, which they would in turn need to obey.

Setting everything about the extended mind theory aside, it is clear that we extend our bodies. Now I want to use my analysis of the extended body as a model for what the extended mind might look like. Given my understanding of extension, the extended mind theory ought to be stated like this:

Call anything that plays the role of mind, but is not mind, an extension of the mind.

Two things are worrisome here. The first is in the clause “but is not mind”. What is not body is relatively easy to figure out–we just appeal to our biological bodies. We can do this because what it is to be a body is to be a biological body. Unfortunately, we can make no analogous appeal to biological minds. We are biological organisms, yes, and it is probable that our minds are realized biologically in the brain. But there is nothing inherently biological about minds. What it is to be a mind is unclear.

The second worrisome thing is that even “the role of mind” is unclear. What do minds do? I mentioned in Section 2 that I couldn’t give a complete answer to this question, and I still can’t. I can, however, give a partial answer, by considering the mental analog of embodiment.

What is enmindment? It is a relation between someone and his mind. As with embodiment, we can distinguish between volitional and sensory enmindment. An m-animator is volitionally enminded in a mind to the extent that he can m-animate it. I say m-animate, not animate, because only bodies (and extensions of the body) can be animated. Animation and m-animation are analogous but not identical. Examples of m-animation include thinking of an elephant, or multiplying six by seven.

An m-subject is sensorily enminded to the extent that his mind delivers m-experience to him. Examples of m-experience include getting an idea, or having it suddenly occur to you that you’ve left the kettle on. Again, m-subject and m-experience are analogous to subject and experience, but they are not the same. I have been using “subject” and “experience” to speak of perceptual experience, and there is nothing perceptual about getting an idea.

Minds, then, get m-animated by m-animators and deliver m-experiences to m-subjects. Minds play more than these two roles, it’s true, but these are good ways to narrow the scope of a terrifyingly broad question.

Instead of asking whether anything that is not mind plays the role of mind, I am now asking whether anything that is not mind can be m-animated or deliver m-experiences. This is almost a tractable question, but the worrisome issue of what counts as not mind remains. I still need an mental analog of the biological body.

I find that analog, I think, in a feature shared by all candidates for extensions of the mind. (Notebooks, iPhones, and the like.) Our interactions with all of these are mediated by perceptual experience. Perceptual experience, not m-experience. I suggest that anything we must interact with through perceptual experience is not part of the the mind, but may yet turn out to be an extension of the mind.

Extended mind theorists might object that I have just rejected their thesis outright. I do not think I have, not in a way that matters. Consider the extended body again. Asking about what is part of the body leads nowhere interesting, but asking about what is an extension of body leads somewhere surprising and important. It turns out we can, in two clear senses, be embodied in things that are not body. Now, I think the question of what is part of the mind is no more interesting than that of what is part of the body. It’s extension that we ought to care about. If it should turn out that we can be enminded in things that are not mind, then we extend into the world that much more profoundly.

If this is not the aim of the extended mind theory, it is the part of the extended mind theory worth aiming for.

Can anything that is not mind be m-animated or deliver m-experiences? I don’t know enough about the nature of thought or belief to give a satisfactory answer to this question, but I will make an effort, mostly in the hope that someone who knows more about thought and belief will take up my approach and answer better.

Suppose I multiply six by seven entirely in my head. I meant this to be a simple example of computation, but it’s probably not computation at all, because I have memorized my multiplication tables. When someone asks “What’s six times seven?”, I just access the relevant belief in my memory. So really this is an example about beliefs.

Can inscriptions in a notebook–multiplication tables, sentences about what I had for breakfast this morning, and so on–count as extensions of the mind? I do not think they can, for the simple reason that I am not volitionally or sensorily enminded in them. I am not enminded in them until I (perceptually) experience them, at which point it is not what’s in the notebook that I m-experience or m-animate, but what’s in my head.

Note that the same applies to dispositional beliefs in the head. I am not sensorily or volitionally enminded in these, either, until I turn them into occurrent beliefs. This is a bit weird. Intuitively, there does seem to be a sense in which I am enminded in my dispositional beliefs. But if I am, it is not the sensory or volitional sense. What sense could it be? This is the question we ought to be asking if we want to know whether dispositional beliefs can be extended. The answer is, unfortunately, beyond the scope of this essay. I leave it to you as an exercise, or to myself for future research. If you want, we can race.

I do not mean to deny that we might come to rely on notebooks or iPhones to store information for us, or that we might enjoy having far more information readily available to us than what’s in the head. “Enjoy” might be too weak a word, in fact. I do not have an iPhone because I do not want to get addicted to having more information readily available to me than what’s in my head. I am not afraid of being addicted in itself. I am addicted to coffee and it brings me great joy. What I am afraid of is habitually outsourcing to the internet work that my head does better. Accessing information with an iPhone may be faster and more elegant than accessing it with a Blackberry, but compared to accessing information in the head, it is slow and clumsy. I endeavor to be less of both.

Thus it delights me that extended calculation, unlike extended belief, seems commonplace. And better. Extended calculation is faster and more accurate than calculation in the head. In the rest of this paragraph, I give an example of the kind of calculation that could be extended; in the next, I give an example of its actually being extended. Suppose I multiply 592 by 2 in my head. (I have not memorized my multiplication tables this far.) There are several algorithms I could use to perform the calculation. I could add 592 + 592, or I could count by twos 592 times, but what I would actually do is very like what I would do on paper. I would imagine writing …

592

x 2

… then I would multiply 2 by 2, imagine writing a ‘4’ in the ones column, multiply 9 by 2, imagine writing an ‘8’ in the tens column, carry the one, and so on until I had imagined writing ‘1,184’ below the horizontal line. So long as all this is happening in my head, I take it that I am enminded in the symbols I m-animate, enminded in the imagined representations of 5, 9, 2, and so on. Now, is there any reason to think that when I do the same this same calculation with a pen and paper, using this same algorithm, I am no longer enminded in the symbols?

If I were to say “Yes,” it would be because in the first case I am volitionally enminded in imagined symbols, while in the second case I am volitionally enminded–if I am volitionally enminded–in actual symbols, in marks on the paper that look like ‘5’, ‘9’, ‘2’, and so on. There is a difference here, it’s true, but it doesn’t strike me as an important difference. It seems to me that actual symbols on paper play precisely the same role as imagined symbols in the head, only they play it better. They are easier to keep track of. Still, it is worth saying how, strictly speaking, I can be enminded in actual symbols instead of imagined ones.

I think it works like this. When multiplying on paper, where am I directing my volitions? Not toward my hand, certainly. Not toward my pen, either. I’m not thinking draw a vertical line in front of the ‘9’. I’m thinking carry the one. What is carrying the one, if not being volitionally enminded in a symbol?

Velleman has suggested that acting on volitions like carry the one might be examples of embodiment, not enmindment. That instead of m-animating imagined symbols in my capacity as m-animator, I am animating actual symbols in my capacity as animator. Neither of us endorses this suggestion, but we think it deserves arguing against.

I will argue against it twice. First, by making a simple appeal to language. “Carry the one,” expresses an action and an object of that action. The object is, I think, a numeral, although one could argue that it is a number. If it is a number, it cannot be animated. Numbers must be m-animated. If it is a numeral, then perhaps it could be animated, but I am not animating it by carrying it. The action expressed by “Carry the one” is not the same action expressed by “Carry those buckets.” Carrying, in the first sense, is not something that an animator could make a body do. Carrying is a mental action.

Suppose, for the sake of this second argument, that I am volitionally embodied in the symbols. This strikes no blow against enmindment. Volitional embodiment, sensory embodiment, sensory enmindment and volitional enmindment are all distinct, and can happen separately, or in various combinations, or all at once. If I am volitionally embodied in the symbols, I can also be volitionally enminded in them. I am enminded in them because they have content. They mean something. What I am getting at here is something you may have been after pages ago, which is a precise characterization of what it is to m-animate. To m-animate is to manipulate meaningful symbols on purpose.

This definition is a bit surprising, because anything in the universe can be a meaningful symbol if I want it to. This hat, I say, represents mind. This salt shaker represents matter. I place the hat over the salt shaker, and I am thinking Mind over matter. I seem have arrived at the strange conclusion that I, in my capacity as m-animator, can extend into almost anything. But take in the view for a minute. This is a rather nice place to have ended up. Your situation may be best described in the words of Meg Stapleton, spokeswoman for Sarah Palin during the 2008 presidential campaign:

From here, the world is literally your oyster.

Clark, Andy, and David Chalmers. “The Extended Mind.” Analysis 58 (1998): 10-23. Print.

Clark, Andy. Letter in London Review of Books 31.6 (2009): n. pag. Web. 13 November 2009.

Shoemaker, Sydney. “Embodiment and Behavior.” Identity, Cause, and Mind. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003. Print.

Velleman, J. David. “Bodies, Selves.” American Imago 65.3 (2008): 405-426. Print.

If there is a better teacher of writing than Pat C. Hoy II of New York University, the world is better than I think. I could not have written this essay without him.

I thank the graduate students of NYU’s philosophy program–Mike Raven, Daniela Dover, and Geoffrey Lee in particular. They hooked me on Philosophy early, and encouraged me to get in over my head.

Bob Frank and Ellen McCollister, my parents, both made helpful comments on early drafts of this essay. I feel lucky that they encourage my interests, even when my interests are as disparate (and as commercially bleak) as philosophy and rock music. I thank the board of the Dean’s Undergraduate Research Fund at NYU, who awarded me a grant to pay for my coffee while I researched and wrote. I thank the staff at Mud, who consistently refuse to charge me for coffee anyway.

Crispin Wright, Laura Franklin-Hall, and Stephen Schiffer were in the audience when I presented this research at NYU’s 2010 Undergraduate Research Conference. They asked insightful questions that helped me think harder, for which I am grateful.

Finally, I thank my thesis advisor, J. David Velleman, whose guidance and criticism throughout this project has been been invaluable. As an arguer, he is both formidable and encouraging. These are not traits that come often enough in tandem.